Digital Sculpture and Modern Art Casting Technologies

Once, a workshop was limited to a table, pieces of wax, and clay. Today, the very air becomes material. A headset on the head, a glove on the hand – and space submits to gesture: a line is born where the palm passes, volume swells from a light wrist movement, surface obeys like warm mass under a chisel. Sculptor, architect, engineer – each in their craft – no longer draws “on paper” but sketches form directly in three dimensions, as if drawing air.

A sketch that once required days grows in minutes: first the silhouette – a pure trajectory, then mass – a few strokes, and now the object holds proportions. Any correction is precise to the smallest detail: from a tiny chamfer to a barely noticeable edge bevel. Scale is obedient like a lens zoom: the model easily becomes palm-height or facade-sized. And all this – without fear of ruining the only copy: every decision is reversible, every version carefully preserved.

Virtual Environments Meet Physical Reality

The digital scene is not confined within the headset – it enters the world. Form can be “placed” in a future museum hall, on a square, in a narrow courtyard – to see how it breathes under daylight, how shadow glides across relief, how metal looks in rain. In this same scene, others are present: author, client, technologist. They walk around the same model, point with their palms where to strengthen a surface, where to soften an edge – and changes happen before everyone’s eyes.

Thus a new discipline forms: first – free sketching in space, then – precision of solid modelling, where every thickness, every radius and draft angle serves future manufacturing. In this rhythm, modern sculpture is born: from living gesture to precise surface, from idea to form ready for embodiment.

Virtual and Real Life: Two Halves of One Psychology

Modern humans already live in two worlds. One is familiar and material: streets, buildings, objects, tangible environment. The second is digital: accounts, pages, portfolios, virtual meetings. For many, this second reality often becomes no less significant: precisely there we demonstrate achievements, form image, enter connections and communities. Virtual appearance sometimes matters more than physical – a resume is more valuable than a handshake, an online profile tells more about us than a business card.

But despite the significance of digital reflection, humans will never dissolve completely in it. Our brains are wired differently: they demand not only visual images. They need smells, textures, sounds, object weight in hand, material sensation under fingers. We don’t trust the world with eyes alone. We recognize it through the totality of senses.

Therefore, virtual forms will multiply and become richer, but they inevitably seek outlet in physical matter. Sculpture created by gesture in air will want embodiment in bronze or stone, so that eyes, hands, and hearing experience it completely. Humans need this second half of experience – touch, walking around an object, sound from contact. As long as this need lives in us, art will not retreat only into digital realm but will seek balance: between virtual image and physical presence of form.

Industrial 3D Printing Technologies for Art Casting

Today, foundry specialists have three industrial additive technology directions at their disposal, each helping transfer digital image to metal in its own way.

Sand Form Printing (ExOne, VoxelJet and analogs): These installations print ready-made molds and cores from silica sand with binder. Artists can bypass traditional tooling: most complex cavities and undercuts are realized directly from digital models. This method is indispensable for large sculptures and unique objects. The disadvantage is rougher surface texture requiring subsequent finishing.

PMMA Burnout Model Printing: Here digital form transforms into polymer models, then burned out in investment casting process. PMMA models can be very large, reproduce complex geometry, and allow printing gating systems together with the product. Surface is slightly granular but becomes suitable for clean molding after wax impregnation. For large artistic objects, this is the most practical path from digital to bronze.

Wax and Photopolymer Printers: These are technologies for maximum precision and finest details. Inkjet wax printers create models from genuine foundry wax, while SLA/DLP photopolymers use special resins that burn out without residue. Their advantage is surface smoothness and jewelry-level detail work. Limitation is relatively small build chambers, so large sculptures must be assembled from sections.

It’s worth noting separately: technologies for direct plastic or metal printing exist, but they don’t replace art casting. Sculpture values not only form but the material itself – its mass, texture, sound, and durability.

Thus, precisely industrial 3D printers – sand, PMMA, and wax – become working tools for the bridge between virtual model and real cast sculpture.

Robotic Processing: From Casting to Finished Artwork

The digital bridge from virtual model to bronze doesn’t end in the casting pit. After metal solidifies and mold breaks away, sculpture is only beginning to emerge. Traditionally, this stage required heavy and painstaking labour: removing runners, cleaning seams, removing adhered sand, subsequent chasing. Today, robotic systems come to the master’s aid, continuing the process’s digital logic.

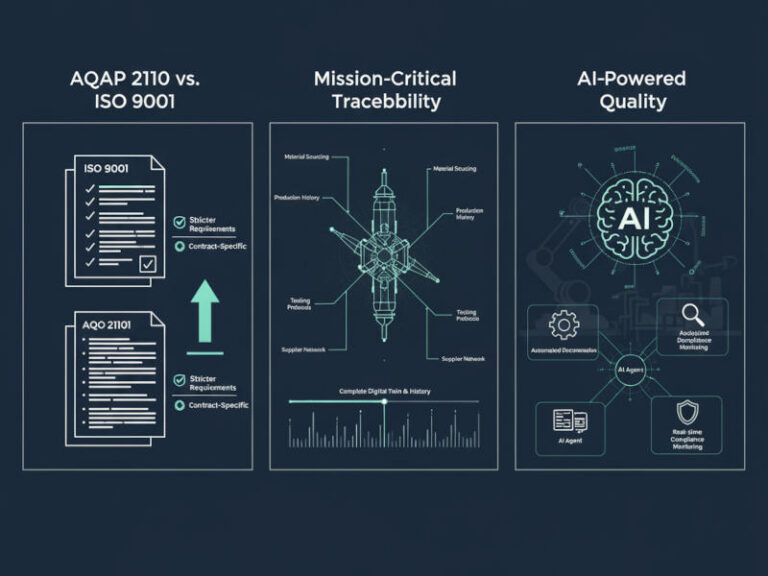

Modern industrial robots equipped with abrasive tools, mills, and grinding heads can perform primary rough work: cutting runners, cleaning surfaces, removing scale. But the key step is integrating artificial intelligence and computer vision. High-resolution cameras and 3D scanners allow systems to “compare” castings with digital standards: where deviations occurred, where runner traces remain, where texture requires finishing.

Algorithms using template and image databases independently determine which areas need processing and direct tools with appropriate force and precision.

AI-Powered Robotic Chasing

Thus emerges new “robotic chasing” – not replacing the master but serving as their digital extension. Machines remove routine, take on heavy and monotonous work portions, leaving artists and chasers the final touch: living intervention, patination, individual accent. This completes the entire cycle: from sculptor’s gesture in virtual air to the shine and tactile completeness of finished cast sculpture.

After all mechanical and robotic stages, the final phase remains – patination. Using various chemical compositions, bronze or other metal surfaces receive unique colour and texture: from classic warm brown to green malachite film, deep blues, or even multicolour iridescence. This alchemy gives sculpture finished character and transforms metal into living surface subordinated to artistic vision.

The Future of Art Casting

Modern art casting production organization, based on digital modelling, additive technologies, and robotic processing, represents not only a new craft development stage but also a fascinating research object. It attracts attention from foundry engineers and specialists from related fields – from materials science to robotics. All these directions fall within our professional interests, and we enthusiastically follow their development, participate in their implementation, and see in them the future of art casting.

This technological convergence creates unprecedented possibilities: where virtual creativity meets traditional craftsmanship, where artificial intelligence serves artistic vision, and where the ancient art of metal casting finds new expression through cutting-edge digital tools. The result is not the replacement of traditional skills but their enhancement – creating pathways for artists to realize visions previously impossible and for foundries to achieve precision and efficiency that honour both innovation and heritage.