Lost-Wax Casting: The Timeless Method Behind Art & Jewellery Masterpieces

The Ancient Origins of the “Lost-Wax” Casting Method

Investment casting, also known as the “lost-wax” method (French: cire perdue), is one of the most ancient techniques for artistic metal casting. This method emerged over 5,000 to 6,000 years ago and was likely invented independently in different regions. Archaeological findings show that by the 4th millennium BCE, artisans in the Middle East and other areas had already mastered this technology.

The principle of the method was simple yet ingenious: first, a model of the object was created from wax. This model was then covered in clay and fired. During firing, the clay hardened while the wax melted away, leaving a cavity that was then filled with molten metal. This innovation made it possible to produce metal objects with far more intricate and delicate designs than casting in open molds, paving the way for a true renaissance in metal artistry.

Some of the earliest known objects made by lost-wax casting come from the ancient Near East. Notably, the Nahal Mishmar hoard (in modern-day Palestine) contained copper ceremonial objects dating to around 3700 BCE, all made using the lost-wax method. Discoveries from the Black Sea region date to a similar period: gold ornaments from the Varna Necropolis graves (Bulgaria, c. 4500–4400 BCE) are considered some of the oldest gold artefacts created via the lost-wax technique.

Ancient Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) is rightfully considered one of the cradles of this art form. As early as the Ubaid and Sumerian periods (c. 3500–3000 BCE), local metallurgists were casting small figurines and jewellery using wax models. One of the earliest surviving castings is a miniature lion pendant from the Uruk IV cultural layer (c. 3300 BCE). Remarkably, Mesopotamia also provides the first written record of the method: a clay tablet from the city of Sippar, dated to the 1780s BCE (the time of King Hammurabi), documents the issuance of a quantity of wax to a foundryman “for the casting of a bronze key,” essentially describing the use of a lost-wax model. This find points to a well-organized craft, where master casters (called ququrrim) already specialized in such techniques.

Ancient Egypt lagged slightly behind the Near East in adopting casting technologies. In the Early Dynastic period, Egyptians primarily forged objects from native copper and gold. However, by the end of the Old Kingdom, around the 23rd–22nd centuries BCE, the first bronze and copper statuettes made by the lost-wax method began to appear in Egypt. In the following centuries, ancient Egyptian jewelers widely used this method to create gold ornaments, such as the complex gold pieces found in the tomb of Tutankhamun (14th century BCE), which researchers believe were cast using wax models.

The Iranian plateau and the Caucasus were also among the most ancient centers of artistic casting. At the Maykop burial site (North Caucasus), magnificent gold and silver bull figurines dating to around 2300 BCE were discovered; they were solid-cast from wax models and are impressive for their fine detail. In Anatolia (modern Turkey), archaeologists excavated the royal tombs of Alaca Höyük (c. 2400 BCE), which contained a large bronze stag cast using a hollow method. These discoveries show that by the 3rd–2nd millennium BCE, the technology had spread rapidly, and artisans in Asia Minor, Iran, and the Eastern Mediterranean had mastered the art of casting complex hollow forms.

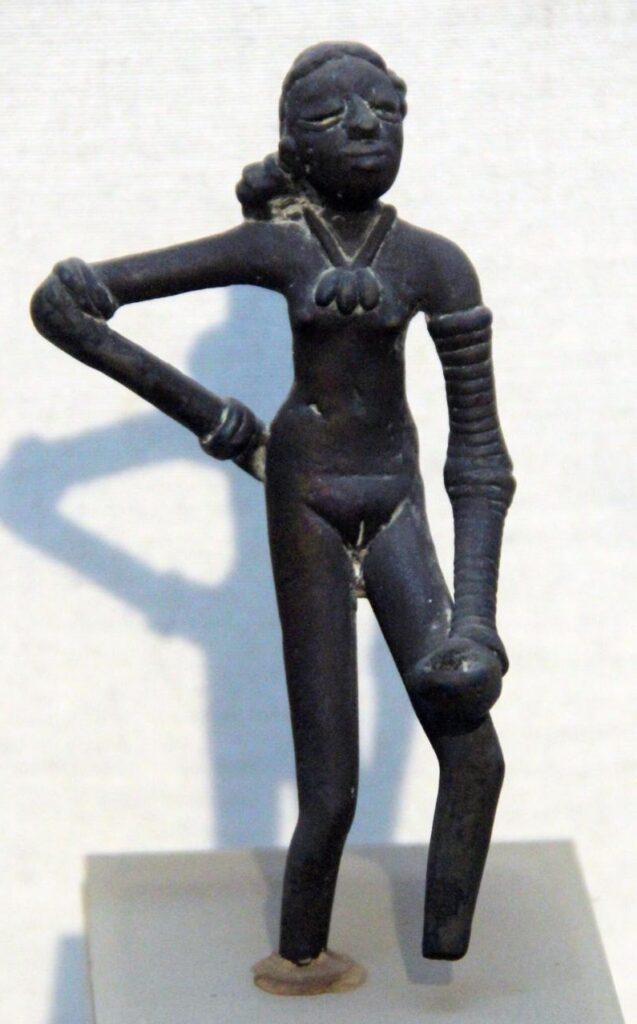

Independently of the Old World, the lost-wax method also appeared in other cultures. In the Indus Valley, the Harappan civilization (c. 2500–2000 BCE) created one of the most famous ancient castings: a small bronze statuette of a nude dancing girl from Mohenjo-Daro. Standing just ~11 cm tall, this figure is striking for its natural posture and detail, serving as a vivid example of the mastery of ancient Indian metallurgists.

Dancing Girl, Mohenjo-Daro, Harappan Civilization, 2700-2100 B.C.E.

Bronze, 10,5 x 5 x 2,5 cm. National Museum New Delhi

Thus, the “cradle” of artistic lost-wax casting can be considered a vast region stretching from the ancient Near East to South Asia. It was in these Eastern cultures that the techniques for casting metal objects of any complexity first originated and flourished. By the end of the Bronze Age (2nd millennium BCE), the method was known on all inhabited continents, though it reached its greatest perfection in the centres of ancient Eastern civilization.

Development in Antiquity and the Middle Ages: The Islamic World and Europe

During classical antiquity (1st millennium BCE – 1st millennium CE), the lost-wax technique continued to be refined. In ancient Greece and Rome, it enabled the creation of the famous life-sized bronze statues. Ancient masters cast hollow figures; for example, Greek sculptures from the 4th–5th centuries BCE (such as the legendary Riace bronzes) were made using the lost-wax method with internal clay cores. A key development of the Roman era was indirect casting, where a master mold could be taken from a single wax model to produce numerous wax copies.

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, complex artistic casting in Europe temporarily declined. In the Early Middle Ages (6th–10th centuries), European craftsmen rarely cast large figures, with the exception of church bells.

The picture was very different in the medieval Islamic world. Despite religious restrictions, Islamic artisans achieved an exceptional level of skill in artistic casting. They created both utilitarian objects and decorative sculptural forms, often in the shape of animals. One of the most famous examples is a bronze eagle aquamanile (ewer) by the master Suleyman, dated 796–797 CE. This magnificent vessel in the form of a bird of prey (~38 cm high), cast in a single piece, is the earliest dated monument of Islamic artistic metalwork. The complex compositions created in Iran and Central Asia by the early 13th century show that local casters had perfected the technique. Islamic craftsmen preserved and advanced the legacy of antiquity at a time when complex artistic casting had fallen into decline in Europe.

The situation began to change in the 11th–12th centuries, as contact between Europe and the East intensified. Through Byzantium and Muslim Spain, examples of Eastern bronze casting reached European artisans, inspiring them to experiment. Art historians note that the first European works clearly modelled on Middle Eastern examples were aquamaniles – ewers for hand washing shaped like animals. By the 12th–13th centuries, casting such hollow figures became widespread in Germany, the Netherlands, and France. The revival of this technique was made possible by “technology transfer” from the East.

By the 12th century, Western Europe had reclaimed its mastery of artistic casting. Between 1001 and 1015, the famous bronze doors of Hildesheim Cathedral (Germany) were cast – a technical feat for the time. Around 1166, in the same region of Lower Saxony, the famous “Brunswick Lion” was cast – the first large-scale animal statue in medieval Europe to be cast entirely in bronze.

The Renaissance and Early Modern Period (15th–18th Centuries)

During the Renaissance, Europe became the global center for artistic bronze casting. By the early 16th century, the technique was so refined that masters could cast large sculptures with exquisite detail. The theoretical foundations of the craft were laid out in treatises such as

De diversis artibus (“On Various Arts”) by the monk Theophilus (c. 1100). Several centuries later, the sculptor and goldsmith Benvenuto Cellini not only masterfully used the ancient technique but also described in detail how he cast his famous statue

Perseus with the Head of Medusa (1545–1554), reviving the secrets of ancient casters.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the lost-wax method remained the primary technique for fine art casting and jewelry. European workshops produced both monumental sculptures and smaller decorative pieces. In Louis XIV’s France, the casting of elegant bronze ornaments for furniture and fireplaces was well-established. At the same time, for mass production, casting in reusable sand or plaster molds became increasingly common. However, whenever complex shapes or a high level of detail was required, masters up to the 19th century still turned to the wax model.

The Modern Era: Industrial Revolution and Digital Technologies

The lost-wax method found a new life during the industrial age. In the late 19th century, it first caught the attention of dentists and later engineers. In 1907, William H. Taggart patented an improved method for the precision casting of dental crowns, marking the first step toward the industrialization of the process.

During World War II, there was an urgent need for precise, complex-shaped metal parts, such as turbine blades for jet engines. Industry turned to an improved version of the ancient technique, and in the 1940s, “investment casting” (the English term for the method) began to be widely used in the aerospace and machinery sectors. By the 1950s, it had evolved into a modern, high-precision process.

In parallel, a revolution took place in the jewelry industry. In the 1930s, the use of rubber molds was introduced to produce multiple wax copies, significantly speeding up the production of jewelry.

Today, lost-wax casting is undergoing a digital transformation. CAD software and 3D printers allow for the creation of virtual models and their physical realization. Printers have emerged that can create patterns from special castable materials (wax-based photopolymers or PMMA plastic), which can be used directly in the casting cycle. Geometric complexity is no longer limited by the skill of a craftsman’s hand; a printer can create any undercut or filigree design. The use of 3D printing dramatically accelerates the process: the time from design to finished casting can be a matter of days.

Digital technologies have also opened up new creative possibilities: 3D scanning can be used to digitize a real object and then cast a miniature copy in metal. As experts note, additive manufacturing combined with the ancient casting technique allows for the realization of the boldest ideas with almost no limitations.

In conclusion, the journey of the lost-wax casting technology is a remarkable story that connects ages. Born in the ancient East, it has travelled through millennia. The medieval Islamic world made a significant contribution to its preservation, and the Renaissance solidified its role as the foundation of artistic casting. Scientific and technological progress has transformed this ancient craft into a high-precision industrial technology and, ultimately, into a medium for digital creativity. Yet, despite computers and printers, the essence remains the same: molten metal still fills the void left by the “lost” wax, creating works as magical today as they were 5,000 years ago.